Dutch families are reconsidering what an ideal family home looks like and where it’s located. Cities are popular among families due to abundant job opportunities and easily accessible amenities. However, the ongoing housing crisis has led to a dominance of small homes, which often cannot accommodate families. A countermovement is needed to create urban communities where families can thrive. We need more affordable homes designed specifically for parents and children. With just a few simple design alterations, we can make homes family friendly and create surprisingly effective urban living spaces.

Too many small homes

Housing demand is immense, and thousands of homes will need to be built in the coming years, with a significant portion in urban areas. From a demographic perspective, there is merit in developing smaller homes targeted at first-time buyers, one- and two-person households, and seniors. However, the misguided assumption – partially inaccurate – that these groups predominantly live in cities while families reside in the suburbs has resulted in the construction of a disproportionate number of small apartments and studios. This trend is driven by economic factors: small apartments provide the most viable business case for developers, especially as lower parking requirements reduce costs. On the surface, it seems to be a win-win situation: municipalities meet their housing targets, and housing corporations and developers secure feasible projects.

An article published in a major Dutch newspaper (NRC) on 2 August 2023, entitled De opkomst van de woonkazerne: steeds kleinere nieuwbouwwoningen (‘The rise of the residential barracks: ever-smaller new-build homes’) highlights that the size of new homes in Amsterdam has more than halved over the past two decades. In 2003, the average size of a new home in Amsterdam was 120 m2, but by 2022, it had dropped to just 47 m2, according to Haakma Wagenaar in the Architecture in the Netherlands Yearbook 2022-2023. This downsizing is not confined to Amsterdam; across Rotterdam, Utrecht, The Hague and the capital, half of the over 10,000 homes completed were smaller than 50m2.

The report De kwalitatieve woningvraag in 2030 (‘The Qualitative Housing Demand in 2030’), published by the Economic Institute for Building in October 2021, reinforces this perspective. It revealed that 80% of planned housing sites are in inner city areas, with 65% consisting of apartments. In contrast, qualitative housing demand shows a clear preference for single-family homes near cities.

Suburban qualities in an urban context

Small homes, typically accessed via corridors and orientated in a single direction, often have floor plans unsuitable for more than one person. The overemphasis on such housing types hinders the development of sustainable urban communities, leaving families with few affordable alternatives and forcing them to move out of cities. Building homes for families does not necessarily mean constructing more ground-access houses in inner cities. Instead, it calls for a smarter approach to housing stock and the creation of homes that incorporate suburban qualities within an urban context.

The ideal of suburban living

Living in poor hygiene conditions, with large families in small homes, continued in cities well into the twentieth century. The Housing Act and the Health Act of 1901 brought an end to these conditions. With the introduction of the new legislation, housing corporations were established, and local authorities received resources to improve housing standards. From then on, the government began constructing housing in a planned and efficient way. Families moved to compact urban neighbourhoods with ample social housing and good amenities such as schools and playgrounds. The development of housing gained momentum, especially after the Second World War, as rapid construction was required to meet soaring housing demands. New housing typologies, such as dual-aspect terraced homes and flats in modernist high-rise blocks set in garden suburbs, reflected an important step in achieving the anti-urban, suburban ideal of the Dutch family. Apartments were spacious and accessed via shared galleries or staircases. The scale of these developments continued to increase, from apartment blocks with only a few levels in the 1950s to megastructures in the 1970s. However, this growth came with consequences. Social control and social cohesion declined. Ground levels were often used for parking spaces and storage units, while the elevation of many homes created a great distance from green surroundings and outdoor play areas. Despite the spacious designs, apartments lacked the desired sightlines and hearing distance needed for children to play outdoors. The wide play-streets along the access galleries turned out to be a utopian ideal. Urban high-rises did not appeal to families: they were seen as too anonymous, too dangerous, and too large-scale. Social problems in various neighbourhoods exacerbated these issues. Suddenly, an alternative became available. With increasing prosperity and ‘a car for everybody’, affordable, ground-access homes with gardens were now within reach for many.

At almost the same time, a countermovement emerged. Some families preferred to continue living in the city. Older districts were revitalized through urban renewal. Cities proved to be perfectly suitable for both children and parents. While urban families often lived in smaller homes with little outdoor space of their own, this was largely compensated for by the urban context, which provided employment nearby and robust amenities. In recent decades, many homes have been adapted to suit families, and successful projects have been realized for this target group. In recent years, however, a new challenge has emerged. While the city has become an attractive place to live for many, good family homes in the heart of the city are scarcely being built, especially in the affordable category.

The (ideal) family home

Families have specific needs when it comes to their homes. Key factors include the size of the dwelling, the floor plan, the availability of outdoor space, and the home’s position relative to the street.

The home: size matters

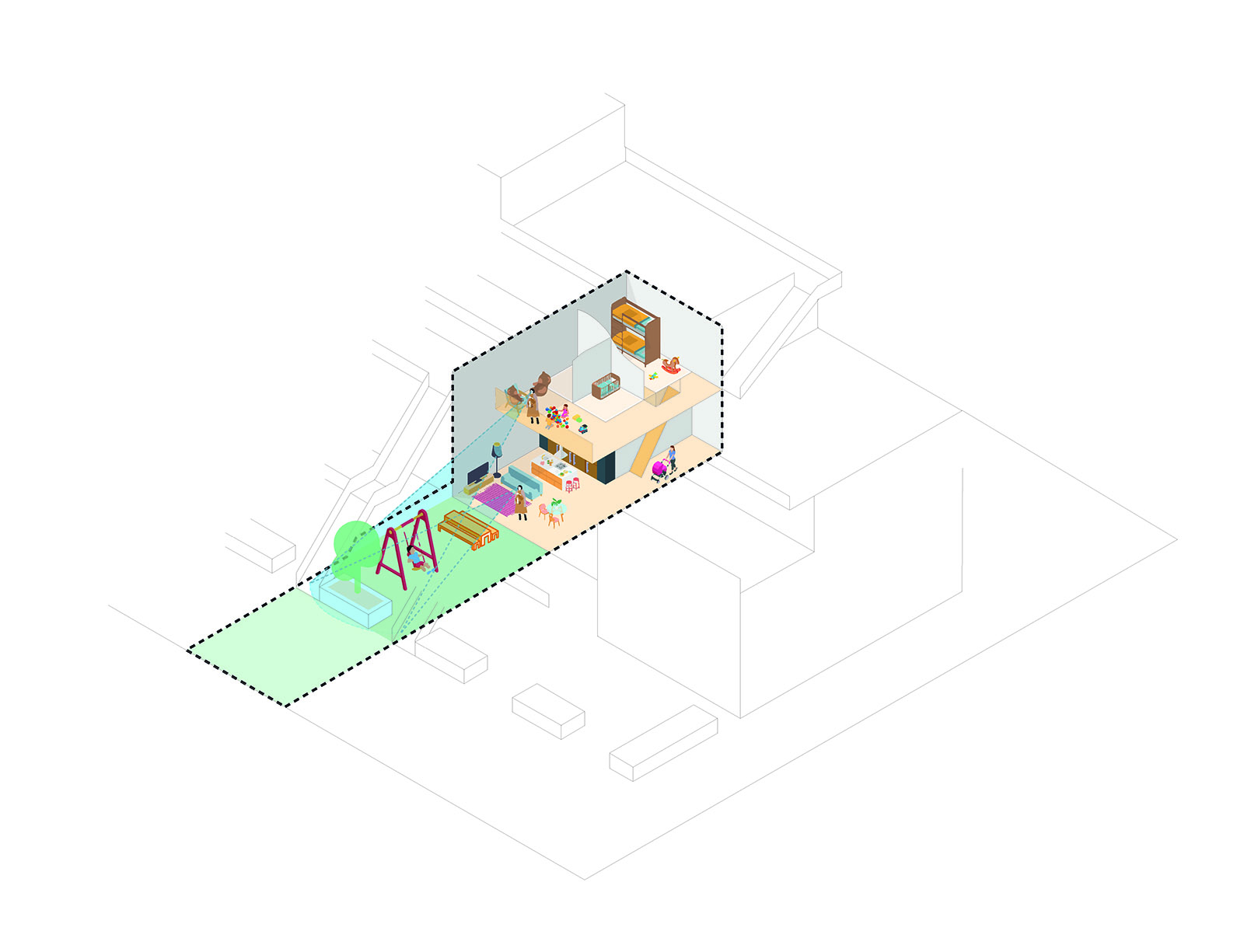

Flexible space in the family home. Image: Urhahn.

Families tend to accumulate belongings, such as strollers, toys, bikes of various sizes, and groceries. Their homes must be easily accessible and provide ample storage space. Additionally, each family member should ideally have their own personal space within the home. Larger dimensions and smarter floor plans can help achieve these goals.

Sufficient size: ‘an extra room’

A family home can be designed compactly to maintain affordability, but certain dimensions are non-negotiable. Corridors should be wide enough to accommodate prams. Storage space should be ample, ideally located on the ground floor or easily accessible without requiring the use of stairs. High ceilings are another valuable feature, as they allow for bunk beds, tall storage units, or even attic space. This is particularly helpful given the sheer volume of toys and other items that take up room. High ceilings also create a sense of spaciousness and allow for more natural light. Multiple levels can enhance privacy through gradations in use, though they are not essential. And, unsurprisingly, children benefit from having their own spaces.

Smart floor plans

The dynamics of family life evolve over time. For young families, the living room and kitchen are central spaces where they spend the most time together. As children grow older and reach adolescence, they begin to seek more privacy in their bedrooms. Therefore, a flexible floor plan is highly desirable. A study can become a nursery, and a guestroom can be converted into a study as needs evolve. Such flexibility should be carefully considered in the design phase.

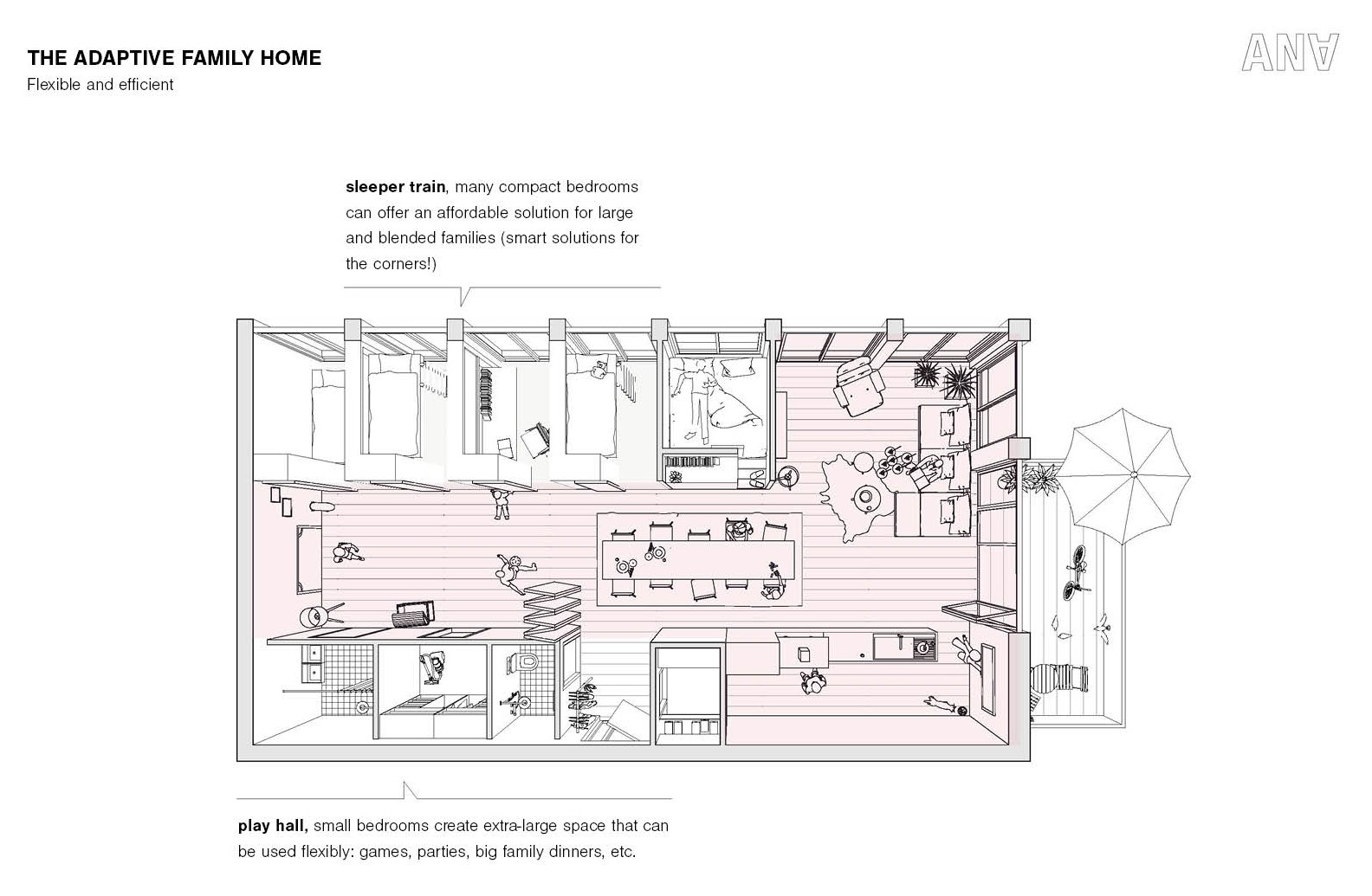

While children’s rooms can be compact to prioritize the layout of main living areas, the design of communal spaces should accommodate children’s needs. For instance, living areas can include smaller domains where children (and later teenagers) can have their own defined spaces. This makes smaller bedrooms more acceptable, as seen in the example of the ‘adaptive family home’ in Section 3.

In certain areas, slightly larger dimensions are not just desirable – they’re essential. A niche in the living room, for example, can serve multiple purposes: a play area, a study corner, or even a guest bed for visiting grandparents. Generous sizing at the entrance, whether as a wide indoor corridor or an outdoor semi-private transition zone, is invaluable for storing strollers, bikes and scooters. A well-sized landing can also double as a convenient space for hanging clothes to dry.

Good family homes and multi-storey housing co-exist harmoniously in ‘De Nieuwe Defensie’. The ground-floor family homes have direct views of a shared courtyard designed for children to play safely. The design ensures a smooth transition between private and public space. Photo: ANA Architecten.

The residential building

Encroachment zone: transition from the private to the public. Image: Urhahn.

Shared facilities within the comlex. Image: Urhahn.

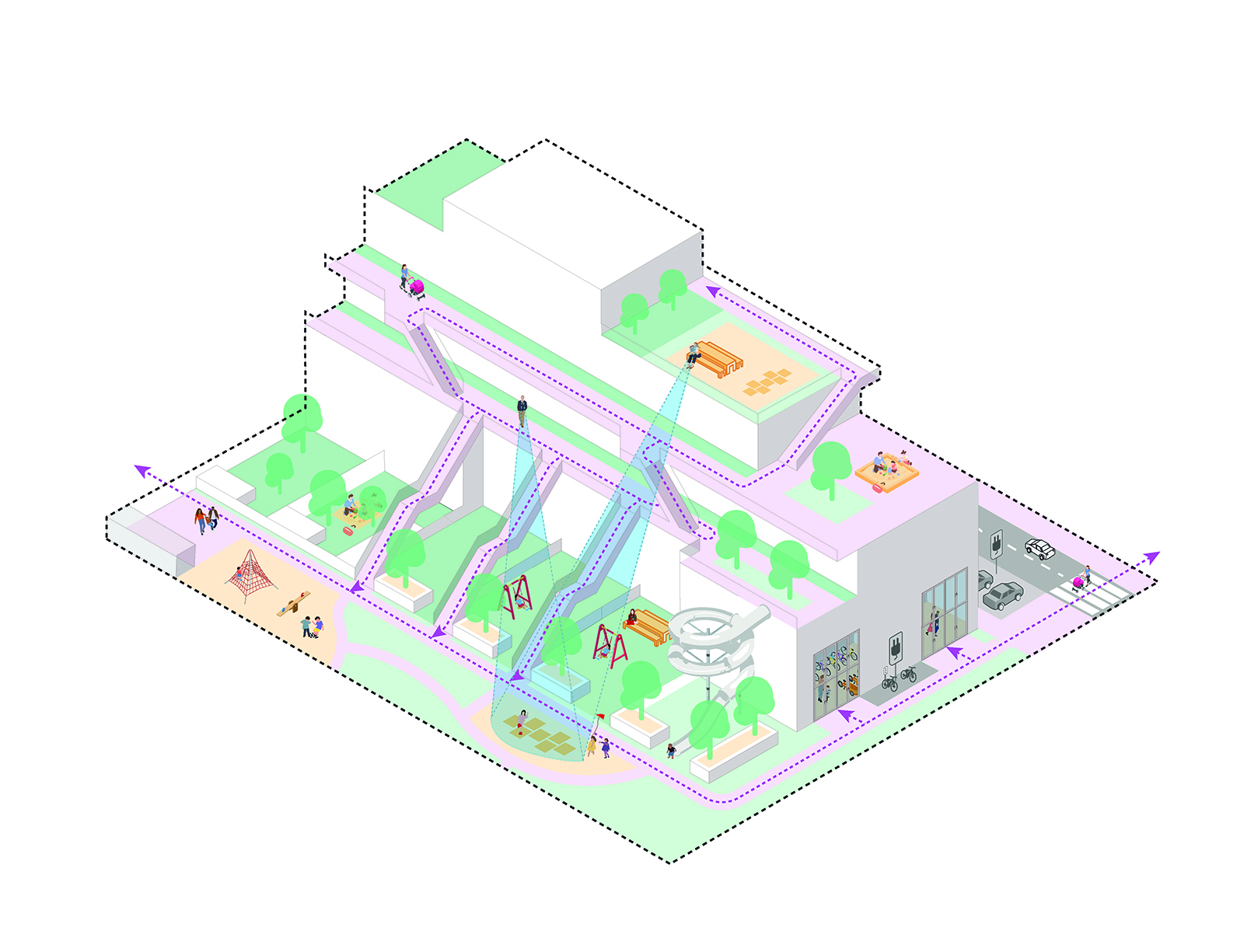

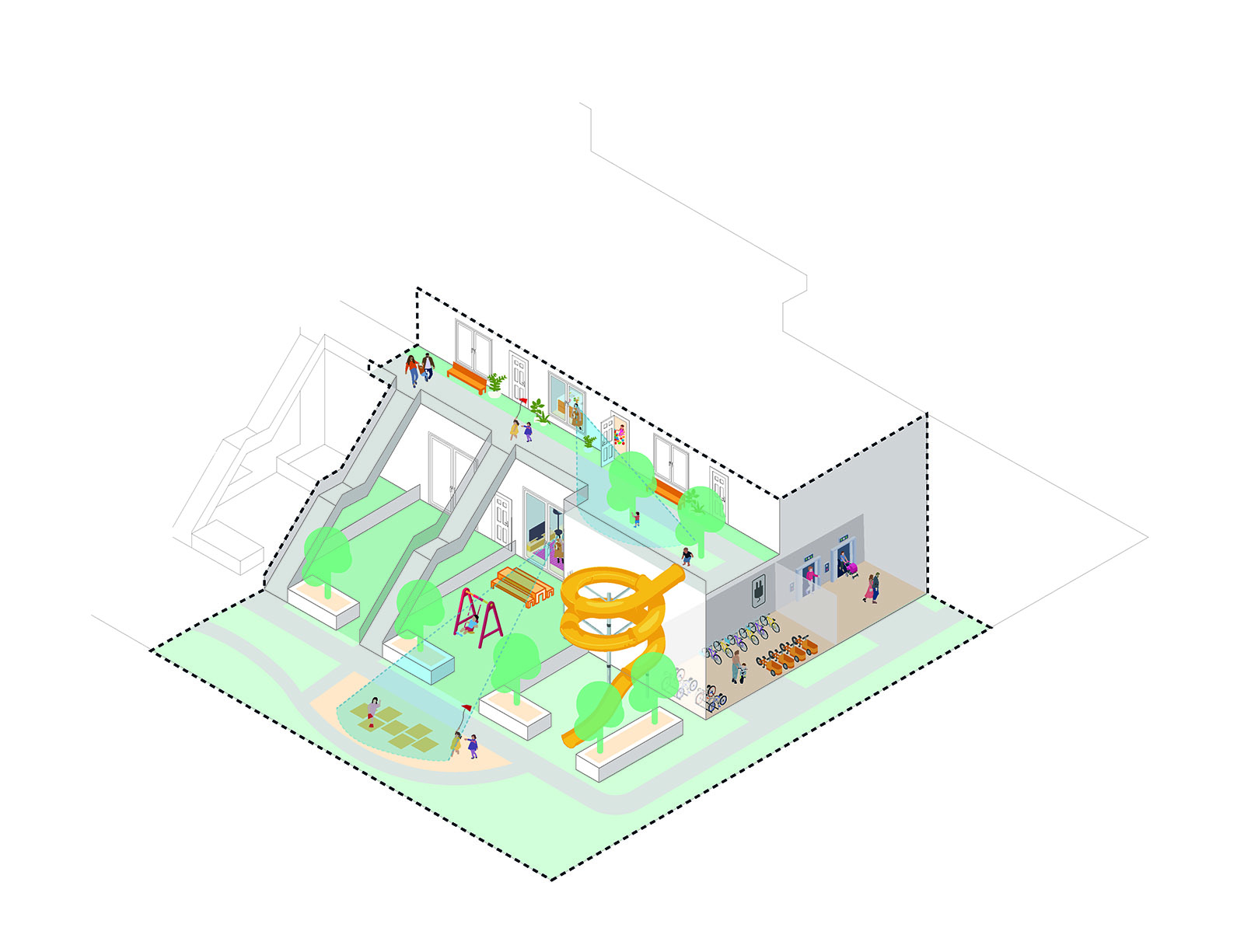

The radius of a child’s activity is naturally limited, making the location of the home within the building, as well as the building’s relationship to its surroundings, critically important. A well-organized floor plan that positions the right functions in the right places can foster social encounters, enhance the functionality of amenities, and promote social safety at the building level.

Maximising use of logistical space

Logistical space serves as the transitional area between private and public spaces. This ‘in-between space’ can be designed to serve functional and social purposes. By increasing its size and viewing it not merely as circulation space but as an area for social interaction and collective outdoor activities, one can significantly enhance its potential.

This space should be enclosed, uncluttered, and aligned with the floor plan of the building. When visible from the home, it becomes a safe zone for children’s outdoor play. The choice of materials is critical: sound-absorbing materials, for instance, can minimize noise from children at play, reducing the risk of disputes with neighbours. By integrating such in-between spaces, the radius of activity for children can naturally expand as they grow older, enabling more independence.

Outdoor space, at various levels

Ideally, every family home should have access to its own outdoor space that is both enclosed and safe. While private outdoor space is limited in size, this allows for more generous collective outdoor spaces, which are best located at ground level to ensure adequate sight lines. At ground level, homes should have direct access to the private outdoor space or to the collective outdoor space. For homes on upper levels, a direct connection to galleries, corridors or collective roof gardens can provide similar functionality. Collective outdoor spaces should be clearly bordered, creating defined boundaries that children can easily understand. Material choices in public areas can further reinforce these boundaries and guide children’s play areas, minimizing potential conflicts over shared spaces.

Transition from private to semi-public and public

The design of the home should align thoughtfully with the outdoor spaces, both private and collective, in and around the building. A seamless connection ensures that parents can easily monitor their children playing outdoors, allows children to explore their environment safely, and facilitates natural interactions among residents, including parents and children.

The layout of the home should reflect a clear transition from the most private areas, such as bathrooms and bedrooms, to more public areas like the kitchen and living room. Ideally, private outdoor space should adjoin the least private areas of the home – such as the living room and kitchen – enabling direct access. Additionally, clear sight lines between homes and collective outdoor spaces are essential to ensure safety and encourage interaction.

Sharing amenities

Collective amenities offer significant advantages compared to traditional family homes. These can include shared parking areas for cars and bikes, access to shared vehicles, multipurpose social spaces, and communal storage for items such as garden equipment or outdoor toys. Collective bike facilities should accommodate a variety of storage needs, including (electric) bikes with child seats, cargo bikes, and children’s bikes of all sizes and shapes.

Shared amenities contribute to the affordability of homes by reducing the need for large private spaces. However, shared amenities rely on fostering mutual trust among residents, as well as a sense of community among families within the same complex.

A slide is attached to the gallery of ‘The Family’ residential building in Delft. The raised play deck provides an accessible space where young children can play and serves as a hub for social interaction among residents. Photo: ANA Architecten.

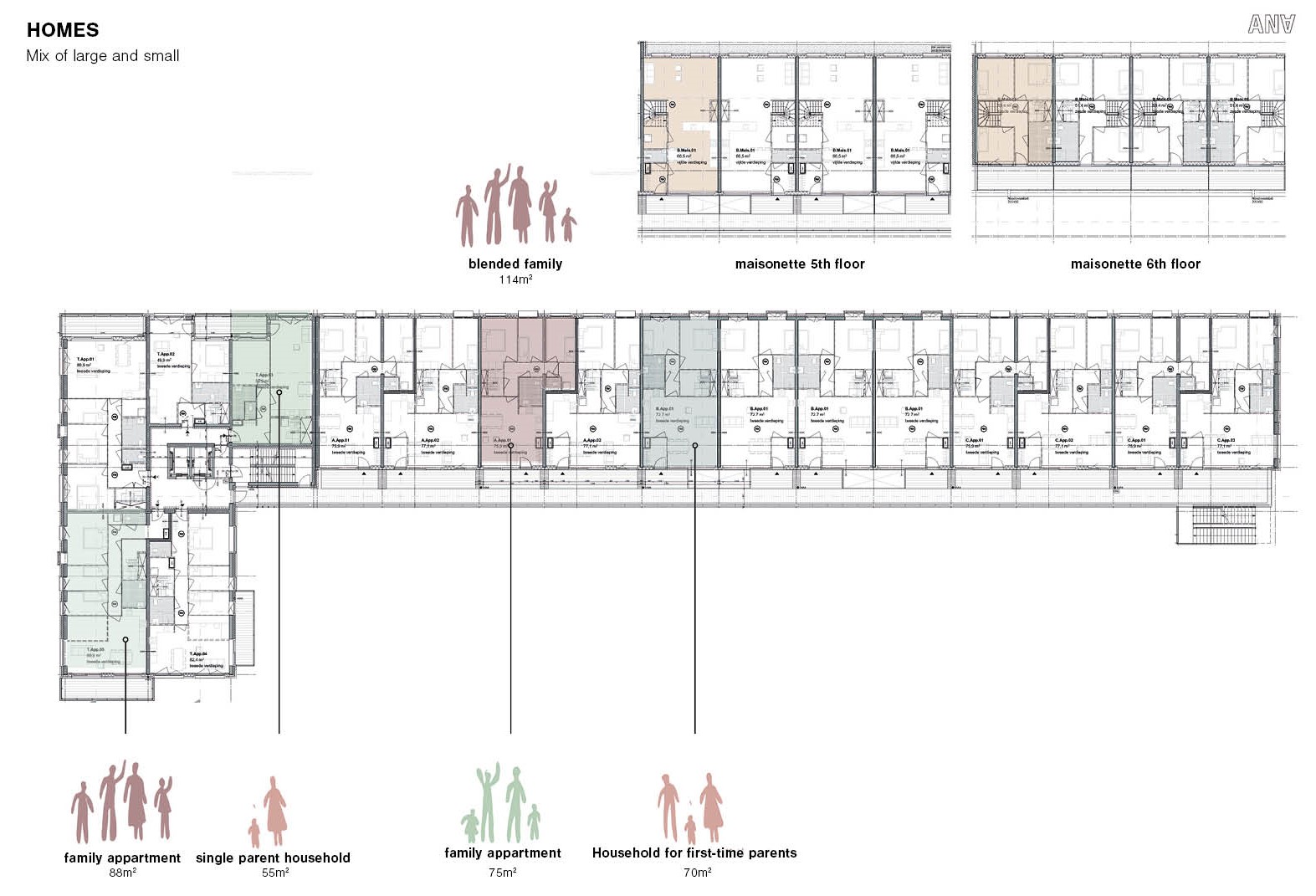

Sufficient variation

Families are diverse and come in all shapes and sizes – two-parent households, single-parent families, large families, small families and patchwork families, to name a few. Each family has unique needs and financial circumstances. As such, designing the ‘ideal family home’ is an unrealistic goal. Instead, there must be a variety of floor plans to accommodate different preferences and living situations.

In the Family Plan study (commissioned by BPD), Ana Architecten explored how floor plans of homes can be optimized for families. Clever layouts allow family needs to be met even within limited surface areas.

The desire to build for families

Achieving family-friendly urban housing requires more than flexible floor plans. Developers, landowners and local authorities must also demonstrate flexibility and creativity. Courageous developers willing to think beyond traditional frameworks and propose innovative solutions are essential to meeting these goals.

One significant challenge is balancing the high parking requirements often associated with family homes with the goals of high-density, affordable development. Reconsidering and reconfiguring parking availability ratios is a crucial step in this process.

Good floor plans and well-designed residential buildings are only part of the equation. Ensuring that families actually occupy these homes is equally important. Raising awareness among families about the availability of urban housing options that meet their needs can encourage them to consider staying in the city. Housing corporations and developers can facilitate this by implementing allocation strategies that help the right target groups find the right homes.

This article was created in collaboration with ANA Architecten, based on a round-table discussion involving architects, developers, local authority officials and representatives from the Van Leer Foundation. A full report on the round-table discussion is available on the website gebiedsontwikkeling.nu via this link.