A city can contribute in two ways to the health of its inhabitants: by minimising health risks and by optimising health opportunities. A city can encourage healthy behaviour. Healthy urbanisation: an appeal to consider health benefits in all urban developments.

A long tradition

Urban design and health share a lengthy history together. Both the Housing Act and the Health Act were drawn up at the start of the 20th century: health ideals lay at the very heart of modern city planning. Hygiene conditions were poor in run-down urban neighbourhoods, good sewerage was lacking, and many people suffered from tuberculosis. Better and healthier living conditions led to the development of modern urban planning and architecture. The residential districts of the pre-war era are a legacy of that movement. Experiments with healthy neighbourhoods were conducted at home and abroad, leading to the English garden cities, the German Siedlungen, and the modernist experiments in Dutch cities. In the 20th century this relation between health and urban planning has taken many forms: in the light, air and space created in the post-war districts of the 1950s and 60s; and in the small-scale residential environments of the so-called cauliflower districts of the 1970s and 80s, which focused on social encounters.

Healthy city or healthy inhabitants?

Since the 1990s the awareness of health has largely translated into environmental targets: the creation of a clean and safe living environment. Much has been achieved in this area. Air has become cleaner, ecological zones now penetrate the city, and sustainable water systems have been developed. This has of course had a very positive effect on the city dweller. The question is, however, whether that city dweller has started to live in a healthier way. Various ‘diseases of prosperity’ have recently taken on epidemic proportions: the number of people with obesity, dementia, depression and cardiovascular diseases is on the rise, and this is partly explained by unhealthy lifestyles. Perhaps we should not refer to these as diseases of prosperity, since many of them are unfortunately linked to low education and income levels. The higher one’s socio-economic status, the healthier one’s lifestyle. We do know that the design of the living environment influences (healthy) behaviour. A clean and safe environment is good for health; movement is medicine. An urban environment can encourage healthy behaviour.

Movement is a choice

In the early 20th century sports amenities emerged and became an integral part of city neighbourhoods. The necessity coincided with the transition from an industrial society to a society based more on sedentary, administrative work. For many people, physical work was a thing of the past, and sufficient movement had to be achieved in another way. Today we see a comparable change as computers increasingly influence our lives. If we no longer want to move, we no longer have to move. Owing to forms of transport such as escalators, cars and mobility scooters, increasing prosperity and technological developments (computers, games, internet services and so on), movement has become a conscious choice. People have to be encouraged to start moving again.

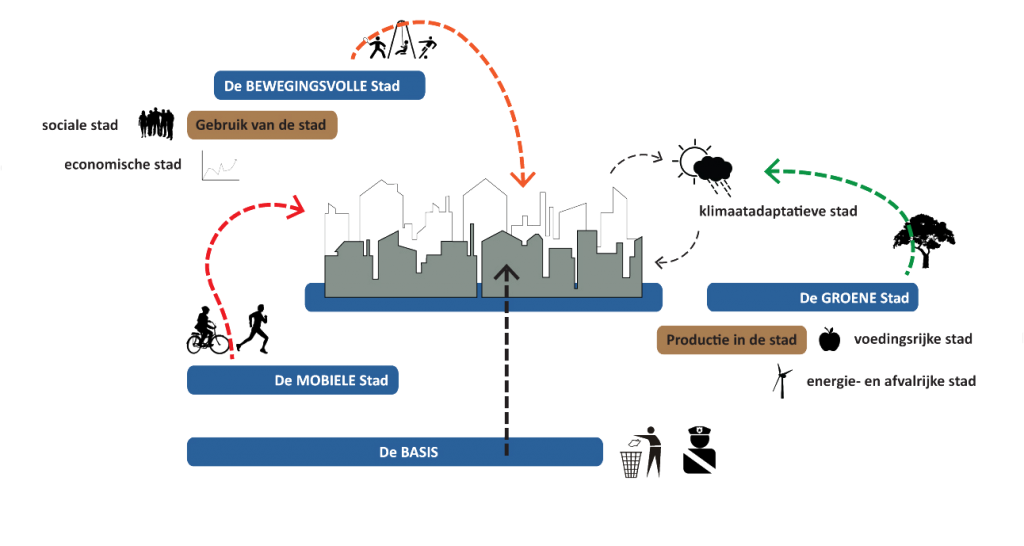

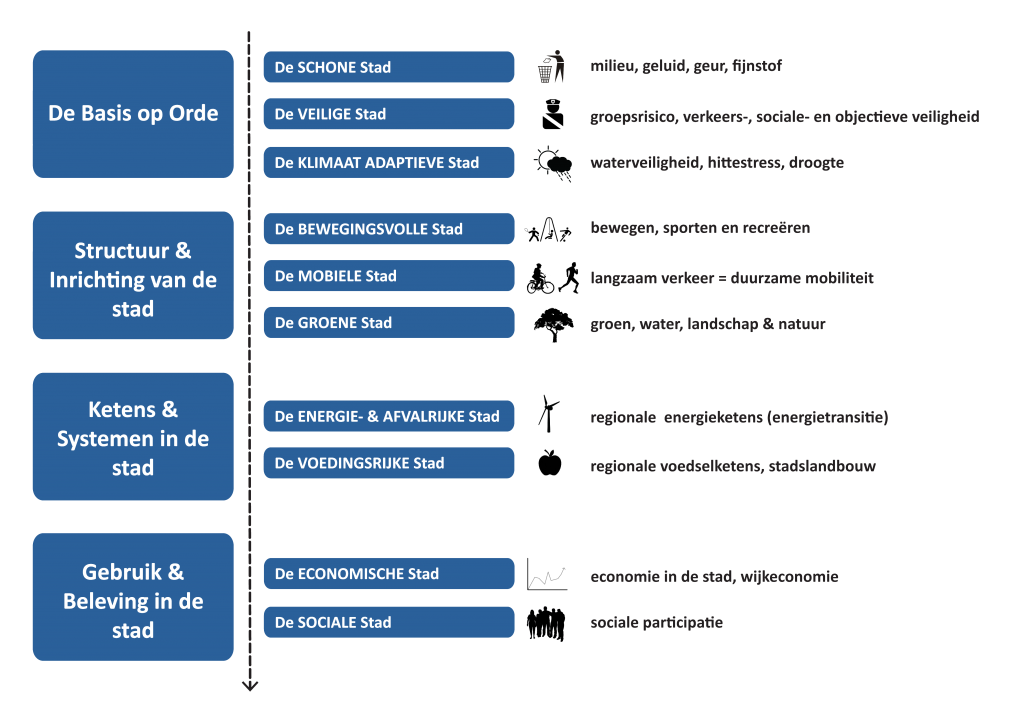

A city that encourages healthy behaviour

A city can stimulate the health of its inhabitants in two ways: by minimising health risks and by optimising health opportunities. Traditional environmental themes such as air quality, safety and noise pollution concern minimising health risks. What is now desirable is to turn our attention to optimising health opportunities. A city can encourage healthy behaviour. More space for movement, sport and games. Priority for bikes (and E-bikes) and walkers instead of cars. Ensure that moving around the city is attractive. Luckily, the city is becoming popular again among young families with children, and elderly people remain living at home for longer. Design the city to cater for these groups.

Health-inclusive design

The era of large area development projects seems to be past. We now see more and more small interventions in the city. Alongside the existing institutions, new players such as housing associations, entrepreneurs and individual citizens are claiming a role for themselves and initiating developments in the city. We make the city together. Let these parties create health benefits as they improve the quality of the city. Let all parties contribute to the design, development and management of the city through ‘health-inclusive’ design: consider the health benefits that can be achieved!

Benefits often lie in small interventions that enable children to cycle more frequently to school, or wider pavements where they can play, or more greenery in the city. Moreover, social initiatives in which residents tackle the development and maintenance of public space can benefit health. Increasing a sense of ‘ownership’ encourages residents to use public space more frequently. This is an appeal to consider the potential to improve health in all urban developments. What this means in concrete terms depends strongly on the social and spatial structure of a place. Experience has taught us that health interventions in a deprived area differ considerably from interventions in a modern, suburban neighbourhood. Every neighbourhood, every place, is unique and calls for unique health-based interventions.

By: Ad de Bont (expert on ‘healthy urbanisation’ at Eindhoven University of Technology and co-founder of the Platform for Healthy Design).

Posted on : 12-02-2015

Images: TUe